Winning a Case: Building a Proof Plan the Jury Understands

“Winning a case” is rarely about having more information. It is about having a proof plan that turns your information into a story jurors can follow, remember, and repeat in deliberations.

A proof plan is not a trial binder or a witness list. It is a simple, explicit map from (1) what the jury must decide to (2) the specific evidence that proves each point, presented in a human order.

What a jury-ready proof plan actually does

A good proof plan forces clarity on three questions:

- What decisions are jurors being asked to make? (Not what happened, but what they must find.)

- What is the cleanest evidence for each decision point? (Not all evidence, the best evidence.)

- What is the simplest way to explain it? (Plain language, concrete verbs, minimal legal jargon.)

When you build this early, your discovery, depositions, motions, and demonstratives all pull in one direction.

Step 1: Build backwards from what the jury will be told

Before you outline a single opening, start with the end:

- Verdict form (or a draft of what you think it will look like)

- Key jury instructions (or the pattern instructions you expect)

- Elements and burdens you must meet

This “backwards” approach keeps you anchored to what matters legally and prevents the common trap of over-proving background facts that do not move any element.

If you need a quick refresher on what counts as relevant evidence, Rule 401 is the simplest starting point: the evidence must make a fact “more or less probable” and the fact must matter to the case. See Federal Rule of Evidence 401.

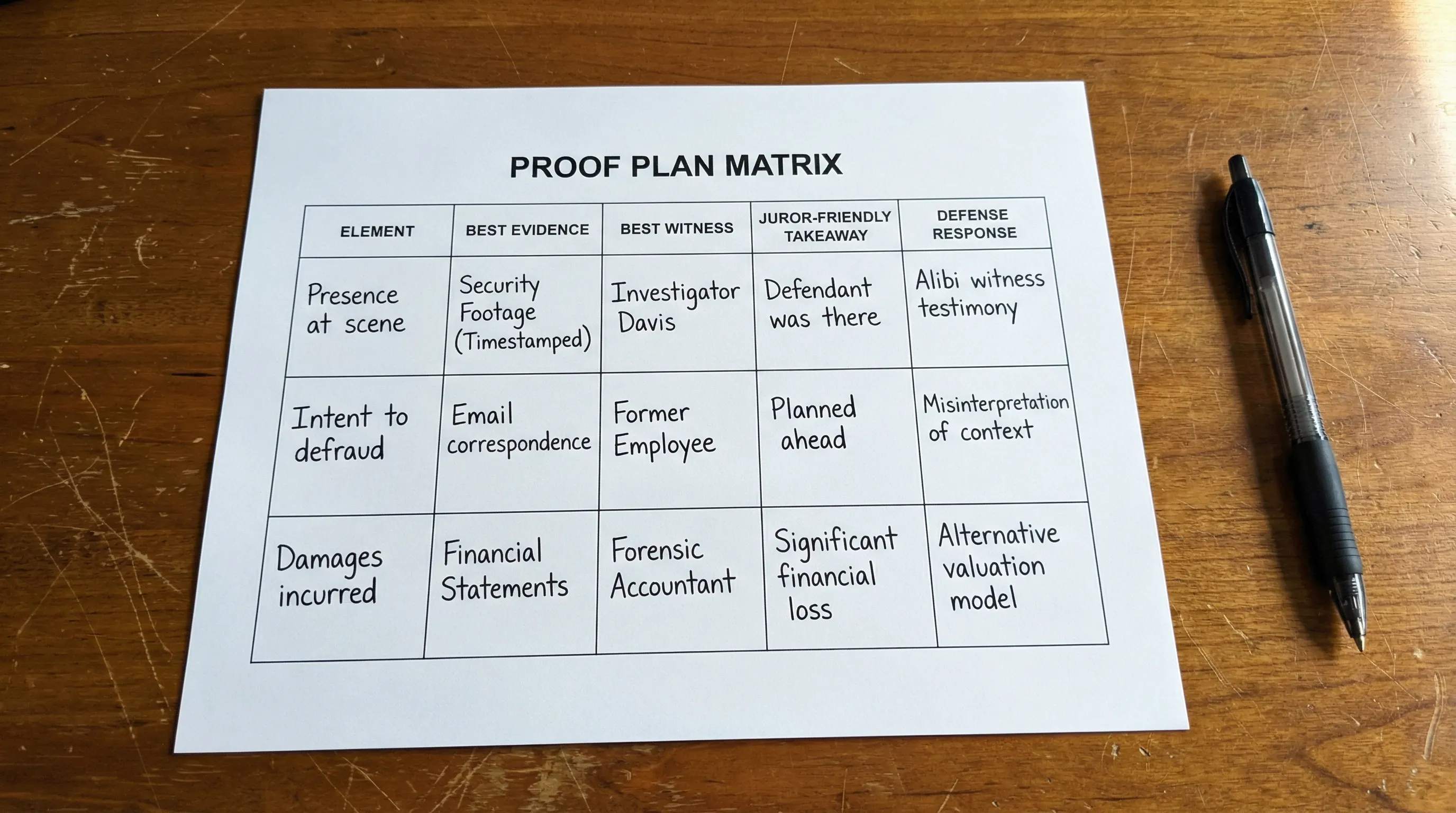

Step 2: Create an elements-to-evidence matrix (the core of the plan)

Your proof plan becomes real when it fits on one page. The best format is a matrix that ties each element to:

- The best document(s)

- The best witness testimony

- The one sentence you want a juror to repeat

- The anticipated defense and your response proof

Here is a simplified template you can copy:

| Issue the jury must decide | Element (plain English) | Best document proof | Best witness proof | “Juror sentence” | Likely defense | Your rebuttal proof |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liability | Duty existed | Policy, contract, statute excerpt | Corporate rep, supervisor | “They were responsible for safety.” | “No duty” | Industry practice, admissions |

| Liability | Breach | Emails, incident report, photos | Eyewitness, expert | “They ignored the warning signs.” | “We acted reasonably” | Timeline + prior similar issues |

| Causation | Cause-in-fact | Medical records, diagnostics | Treating physician | “The incident caused the injury.” | “Pre-existing condition” | Baseline records, differential dx |

| Damages | Reasonable value | Bills, wage records | Economist, employer | “These losses are real and documented.” | “Inflated/avoidable” | Coding notes, mitigation steps |

If you cannot fill a cell, you found a gap worth solving now, not during opening.

Step 3: Translate legal elements into a teachable story

Jurors do not deliberate in “elements.” They deliberate in common-sense questions.

Try this translation rule:

- Replace abstract nouns with verbs.

- Replace standards with comparisons.

- Replace “therefore” with a picture or timeline.

Examples:

- “Breach of duty” becomes “They broke the safety rule they knew about.”

- “Causation” becomes “This is what changed after the incident, and why nothing else explains it.”

- “Reasonable medical expenses” becomes “These are standard charges for necessary care, and the records show it.”

For juror comprehension, plain language is not a style preference, it is a performance advantage. Research summarized by the National Center for State Courts supports that clearer instructions improve understanding (and reduce confusion-driven outcomes). See the NCSC’s work on plain language jury instructions.

Step 4: Put your proof in a sequence the brain can keep

A jury-friendly proof order is usually:

- The promise or rule (what should have happened)

- The moment it broke (what actually happened)

- The ripple effects (medical course, wage loss, life impact)

- The receipts (documents that corroborate)

Chronology is your default structure because it reduces cognitive load. Use “chapters” with consistent labels (same words in opening, same words on slide titles, same words in closing).

A practical test: if your timeline needs constant sidebars to explain itself, you may be mixing issues that should be separate chapters.

Step 5: Build defense into the plan, not around it

A proof plan that ignores the defense is not a plan, it is a wish.

Add a “defense column” to every key issue:

- What do they want jurors to believe instead?

- What is their cleanest exhibit?

- What is your cleanest contradiction? (ideally a document or admission)

This is where your depositions become targeted. You are not taking testimony, you are collecting the few sentences that neutralize the defense narrative.

Step 6: Turn the plan into litigation outputs, faster and with fewer misses

Once your matrix is solid, you can generate case materials consistently:

- A demand letter that mirrors the proof order

- A medical summary that supports causation and damages (not just a record recap)

- Deposition outlines keyed to gaps in the matrix

- Trial exhibit lists and “why it matters” notes

If your team is buried in documents, tools like TrialBase AI can help by analyzing uploaded materials and producing litigation-ready drafts (medical summaries, deposition outlines, demand letters, and other trial materials) in minutes. The point is not automation for its own sake, it is freeing attorney time to pressure-test the story and the proof.

Step 7: Make professionalism part of the proof (yes, it affects comprehension)

Jurors judge credibility with more than words. Sloppy exhibit labeling, inconsistent visuals, and a disorganized “table presence” all create friction that competes with your message.

That includes the basics like consistent binders, clean demonstratives, and coordinated courtroom logistics. In longer trials, some teams even standardize practical details (for example, matching team attire for in-court days) to reduce distraction and look organized. If you ever need custom production support for physical materials, working with an experienced manufacturing partner such as Arcus Apparel Group can be a straightforward way to source consistent, professional apparel for a team.

A quick proof plan audit before you lock in trial themes

Read your matrix and answer these out loud:

- Can I explain each element in one sentence without legal jargon?

- Do I have one “best” exhibit per element, not ten decent ones?

- Is my causation story a timeline jurors can repeat?

- Does every likely defense have a specific rebuttal proof?

- Does my opening order match my closing order?

If you can confidently answer “yes,” you are not just preparing. You are building the kind of structure that helps jurors reach the verdict you need.

.png)