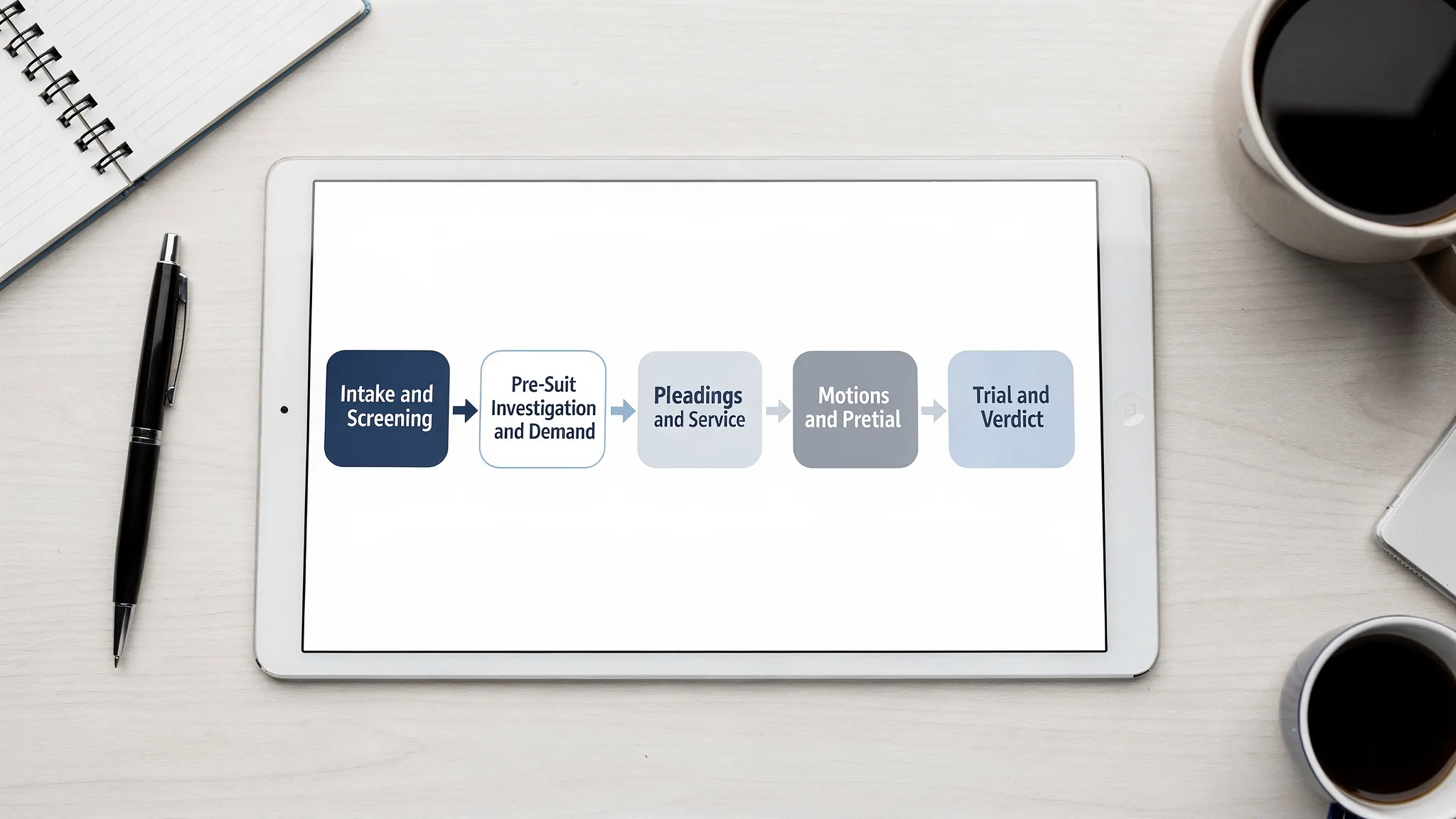

Process of Litigation: Key Stages From Intake to Trial

Litigation is often described as a “journey,” but in practice it is closer to a tightly managed project with hard deadlines, evolving facts, and constant judgment calls. Whether you handle personal injury, employment, commercial disputes, or professional liability, understanding the process of litigation helps you (and your client) make better decisions early, avoid preventable delays, and prepare for the leverage points that actually drive outcomes.

What follows is a practical, stage-by-stage walkthrough of key phases most civil cases pass through, from intake to trial (and the major work product created along the way). Exact steps and terminology vary by jurisdiction, court, and case type, but the structure is remarkably consistent.

This article is general information, not legal advice.

Stage 1: Client intake and case screening

Intake is where strong cases are built (or quietly avoided). The goal is to decide, quickly and defensibly, whether the matter is viable, what evidence must be preserved, and what the first 30 to 60 days of work should look like.

What happens during intake

A high-quality intake typically includes:

- Conflict checks and engagement documentation (retainer, fee agreement, scope).

- Basic timeline capture (who, what, when, where, and how).

- Liability theory (duty, breach, causation, damages, or the analogous elements for your claim).

- Early damages mapping (medical expenses, wage loss, future care, business loss, emotional distress, punitive exposure where applicable).

- Statute of limitations and notice requirements (and any tolling issues).

- Evidence preservation planning (spoliation risks, ESI sources, surveillance video retention, vehicle black box data, social media).

Intake deliverables that make later litigation easier

| Intake deliverable | Why it matters later | Common pitfalls if skipped |

|---|---|---|

| Clean chronology (dated events list) | Forms the backbone of pleadings, discovery, and trial themes | Inconsistent timelines across documents and witnesses |

| Parties map (who is involved, roles) | Helps identify defendants, employers, insurers, and witnesses | Missing a key entity, service problems, insurance surprises |

| Evidence inventory | Prevents “we didn’t ask for that” moments | Lost video, overwritten texts, missing employment records |

| Medical/providers list (if injury) | Speeds record requests and damages proof | Months of delay in medical summaries and causation analysis |

Many firms now use structured intake workflows so the same critical data is captured every time. If you use AI in intake, the best use is organizing and summarizing what you already have, not making the initial liability call.

Stage 2: Pre-suit investigation and demand (or early resolution)

Before filing, most cases benefit from targeted fact development. This stage is about turning a client narrative into a provable theory, and testing whether the dispute can be resolved without incurring full litigation costs.

Core tasks in pre-suit

Pre-suit work commonly includes:

- Collecting records (medical, employment, repair estimates, incident reports, contracts, communications).

- Identifying insurance coverage and policy limits.

- Interviewing witnesses and preserving statements.

- Evaluating comparative fault, causation vulnerabilities, and damages support.

- Building a settlement package that is easy for an adjuster, defense counsel, or risk manager to evaluate.

Demand letters and settlement positioning

A persuasive demand letter is rarely just rhetoric. It is a structured argument with exhibits that anticipates the defense story. Strong demands generally:

- State a clear liability theory tied to evidence.

- Present damages in a verifiable format (billing, wage documentation, future care support).

- Explain causation simply.

- Include a settlement number with reasoning (and any time-limited terms, when appropriate).

This is also where litigation support tools can save hours. For example, TrialBase AI is designed to help legal teams transform uploaded documents into litigation-ready work product such as demand letters and medical summaries in minutes, with attorney review and case-specific editing still controlling the final output.

Stage 3: Pleadings, filing, and service

If pre-suit resolution fails (or timing requires immediate filing), the case moves into formal litigation. The pleading stage frames the dispute and often sets the tone for discovery and settlement.

Key milestones

- Complaint/petition filed: alleges claims, identifies parties, and requests relief.

- Service of process: proper service is foundational; defects can delay everything.

- Answer and affirmative defenses: the defense narrative begins here.

- Early motions: motions to dismiss, motions to strike, or jurisdiction and venue challenges.

- Removal/transfer (where applicable): state to federal removal, venue transfer, forum non conveniens.

Practical focus

At this stage, you want alignment between:

- The story in the complaint.

- The documents you already have.

- The discovery plan you will execute.

A common avoidable mistake is pleading a broad set of claims that are not supported by your current evidence or that complicate damages proof. A narrower, well-supported theory can be more effective and easier to prove.

Stage 4: Early case management, disclosures, and ADR planning

Courts increasingly expect early organization and realistic scheduling. This phase varies widely by jurisdiction, but it often includes initial disclosures and a scheduling order.

In federal practice, early disclosures and discovery planning are influenced by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26. Even in state court, similar concepts show up in scheduling conferences and local rules.

What you are building here

- A discovery plan that matches your burden of proof.

- An initial witness list and document categories.

- A realistic case calendar (especially for expert deadlines).

- An ADR strategy (informal settlement talks, mediation timing, early neutral evaluation).

Good teams treat this stage like setting the project architecture: naming conventions, repository structure, review responsibilities, and privilege protocols.

Stage 5: Discovery (written, ESI, and depositions)

Discovery is where cases are won, lost, or priced. It is also where time and budgets can spiral if the team is not disciplined.

Written discovery

Most cases involve some mix of:

- Interrogatories.

- Requests for production.

- Requests for admission.

- Subpoenas to non-parties.

The goal is not just “getting documents.” It is building admissible proof, narrowing disputes, and uncovering the defense’s best facts early enough to respond.

ESI and modern discovery realities

Electronically stored information (ESI) can include email, texts, Slack/Teams messages, call logs, GPS data, and app metadata. The litigation team needs early clarity on:

- Where key data lives.

- Whether holds were issued.

- What format productions will use.

- How to handle privilege, redactions, and confidentiality.

Depositions

Depositions translate document facts into human testimony. The best deposition prep typically combines:

- A tight outline aligned to your elements and themes.

- Exhibits that are chronologically organized.

- Targeted impeachment points.

- A plan for admissions that matter at summary judgment and trial.

This is another area where AI can help with speed, for example by generating deposition outlines from a record set, while the attorney ensures accuracy, tone, and strategic sequencing.

To keep discovery work product consistent, many teams standardize outputs:

| Discovery activity | Work product you should expect | Quality check that prevents rework |

|---|---|---|

| Document review | Issue tags, chronology updates, key-exhibit list | Spot-check citations back to Bates numbers |

| Written discovery responses | Draft responses and objections, privilege log inputs | Confirm consistency with protective order and local rules |

| Depositions | Deposition outline, exhibit set, testimony digest | Verify admissions are captured with page/line citations |

| Expert discovery | Materials list, expert file index, rebuttal themes | Ensure assumptions match the evidentiary record |

Stage 6: Dispositive motions and pretrial preparation

As discovery closes, the case shifts from “finding facts” to “deciding what will be tried.” Two tracks run in parallel: motions practice and trial build.

Dispositive motions

Common motions include:

- Summary judgment: argues there is no genuine dispute of material fact requiring trial (see FRCP 56 for the federal standard).

- Daubert/Frye-type challenges (jurisdiction dependent): attacks expert reliability or fit.

- Motions in limine: seeks to exclude or limit evidence before the jury hears it.

Pretrial deliverables

Even when a case settles “on the courthouse steps,” the work that drives that settlement often looks like trial prep:

- Final witness list and exhibit list.

- Trial brief(s).

- Proposed jury instructions (if applicable).

- Updated damages model with citations.

- Theme development and demonstrative planning.

If your team has maintained a clean chronology and exhibit index since intake, pretrial becomes assembly rather than excavation.

Stage 7: Trial (and the path to verdict)

Trial is the highest-stakes stage, but it is not where most cases are decided. Many cases resolve after a key deposition, after expert reports, or after the summary judgment ruling. Still, preparing as if trial is real is often what creates credible leverage.

Typical trial sequence (civil)

- Jury selection (voir dire), if a jury trial.

- Opening statements.

- Plaintiff’s case-in-chief (witnesses, experts, exhibits).

- Defense case.

- Rebuttal, as permitted.

- Closing arguments.

- Jury instructions and deliberation.

- Verdict.

- Post-trial motions and judgment enforcement (or appeal preservation).

The strongest trial teams focus less on volume and more on coherence: a small set of themes supported by a small set of powerful exhibits and credible witnesses.

The “hidden” stage: communication and team execution

Many litigation delays have nothing to do with law and everything to do with communication: inconsistent client updates, unclear assignments, and uneven deposition readiness.

Two practical improvements make a measurable difference:

- Standardize conversations that recur (intake expectations, medical treatment compliance, discovery obligations, deposition coaching, mediation preparation).

- Practice high-pressure scenarios with staff and attorneys, especially for objection handling and witness preparation.

Some firms borrow training techniques from sales and customer service because the underlying skill is the same: clear communication under pressure. Tools like AI roleplay training can be a useful way to rehearse difficult conversations and improve team consistency, even though they are not litigation platforms.

Where AI fits in the litigation process (responsibly)

Used well, AI does not replace legal judgment. It compresses the time between “documents received” and “work product drafted,” which can help teams litigate faster and more consistently.

High-value, low-drama AI use cases

- Document summarization with citations back to the source.

- Medical record summaries and treatment timelines.

- Drafting demand letters from a defined fact set.

- Generating deposition outlines based on pleadings, key documents, and issues.

- Creating trial prep materials (witness overviews, exhibit descriptions) for attorney refinement.

What to keep in human hands

- Strategic decisions (what claims to bring, what concessions to make, when to settle).

- Privilege and confidentiality calls.

- Final filing review (accuracy, tone, compliance with local rules).

- Ethical compliance, supervision, and client counseling.

TrialBase AI positions itself in that “draft and organize” lane: AI-driven document analysis that produces litigation-ready outputs like demand letters, medical summaries, deposition outlines, and trial materials, with a unified workflow to help legal teams move from intake to verdict more efficiently.

A practical way to think about the process of litigation

Litigation is easiest to manage when each stage has a defined purpose:

| Stage | Primary purpose | “Done means” |

|---|---|---|

| Intake and screening | Confirm viability and preserve evidence | You can articulate claims/defenses and deadlines confidently |

| Pre-suit investigation | Turn the story into proof, test resolution | You can support liability and damages with documents |

| Pleadings | Frame disputes and preserve theories | Claims and parties align with evidence and goals |

| Case management | Set the rails for discovery and experts | A calendar exists that you can actually meet |

| Discovery | Obtain admissions and evidence for motions/trial | You can prove each element with exhibits and testimony |

| Motions and pretrial | Narrow issues and build the trial package | Trial materials are organized and defensible |

| Trial | Present a coherent story with admissible proof | Verdict (or settlement driven by trial readiness) |

If you want one operational takeaway: treat every stage as producing assets for the next stage. A chronology built at intake becomes the index for your demand package, deposition exhibits, and trial timeline.

Closing perspective

Understanding the key stages in the process of litigation is not just academic. It helps you allocate effort where it matters, avoid deadline chaos, and build leverage through credible preparedness. When your team consistently turns documents into structured work product (summaries, outlines, exhibit lists, and trial materials), you reduce rework and increase the odds that negotiations, motions, or trial unfold on your terms.

.png)