Lawyer in Trial: Real-Time Habits That Win the Record

Trials are won twice, once in the room and once on appeal. The lawyer in trial who consistently “wins the record” is not just persuasive, they are precise. They make it easy for the judge to rule correctly in the moment, and for a later reader (law clerk, appellate panel, mediator, adjuster) to understand exactly what happened and why it mattered.

Below are real-time courtroom habits that reliably produce a cleaner transcript, sharper rulings, and fewer preventable problems.

What “winning the record” actually means

A strong record is one where:

- Your positions are stated clearly and tied to the correct legal standard.

- Objections are specific, timely, and ruled on.

- Exhibits are authenticated, offered, admitted (or excluded) with the basis preserved.

- Key facts are anchored in testimony, not just in closing argument.

If you practice in U.S. courts, it is worth revisiting the mechanics of preservation, including what must be on the record to claim error later (see Federal Rule of Evidence 103). The point is practical: you can be right and still lose if the transcript does not show the “why” in a usable way.

Real-time habits that win the record

Speak for the transcript, not for the moment

Courtrooms are noisy, fast, and full of shorthand. Transcripts are not. Build the habit of saying the complete thought.

Examples that help the record:

- “For the record, counsel just stated X. Our position is Y.”

- “Let the witness finish, then I have a follow-up.”

- “May the witness identify the document by date and author?”

Also, avoid head nods, pointing, or “this one” when discussing exhibits. Use exhibit numbers and page or Bates ranges.

Object like you want the judge to rule now

Most “weak objections” fail because they are incomplete. “Objection” is a sound, not a basis.

A record-winning objection is:

- Timely (before the answer when possible)

- Specific (hearsay, foundation, relevance, 403, speculation, improper character, etc.)

- Tethered to what you want (strike, instruct, limit, sidebar, continuing objection)

When you can, add one sentence that tells the court the fix:

- “Objection, foundation. If counsel lays the time, method, and chain of custody, we can revisit.”

That sentence often turns a debate into a ruling.

Make the judge’s reasoning easy

Winning the record is partly helping the court articulate a defensible decision. If you are asking for admission, exclusion, or a limitation, do the framing work:

- State the rule or standard in plain English.

- Apply it to a specific fact in the record.

- Offer the narrower alternative if you can live with it.

This is not about sounding academic. It is about giving the court a clean path.

Run exhibits like a system, not a scramble

Exhibit problems create the messiest transcripts. A simple, consistent workflow keeps you out of side disputes:

- Pre-identify exhibits by number and a short description.

- When using a document with a witness, lock down what it is before you read from it.

- Say “I move to admit Exhibit X,” then pause for the ruling.

- If excluded, make an offer of proof in a crisp, organized way.

Here is a quick reference you can keep in your trial binder:

| Habit | What it prevents | Record-friendly language |

|---|---|---|

| Use exhibit number + Bates page every time | “Which page are we on?” confusion | “Directing you to Exhibit 12, Bates 00452.” |

| Authenticate before you argue from it | Foundation objections and wasted time | “Do you recognize this document? How do you know it’s accurate?” |

| Offer, then wait | Silent “admissions” that are unclear on appeal | “Your Honor, move to admit Exhibit 12.” |

| If excluded, proffer | Missing substance of excluded evidence | “For the record, the exhibit would show…” |

Impeach in a way that reads cleanly later

Effective impeachment is structured. The transcript should show the sequence, not just the drama:

- Commit the witness to the current version.

- Mark the prior statement with date, source, and page/line.

- Read the exact prior language.

- Ask the witness to reconcile.

If you skip these steps, the later reader may not understand what the contradiction actually was.

Use short “record resets” after sidebars and breaks

Sidebars, bench conferences, and off-the-record discussions happen. What matters is what comes back onto the record.

A useful habit is a 10-second reset:

- “Back on the record, the court has ruled X. We are proceeding with Y.”

It reduces ambiguity and protects everyone.

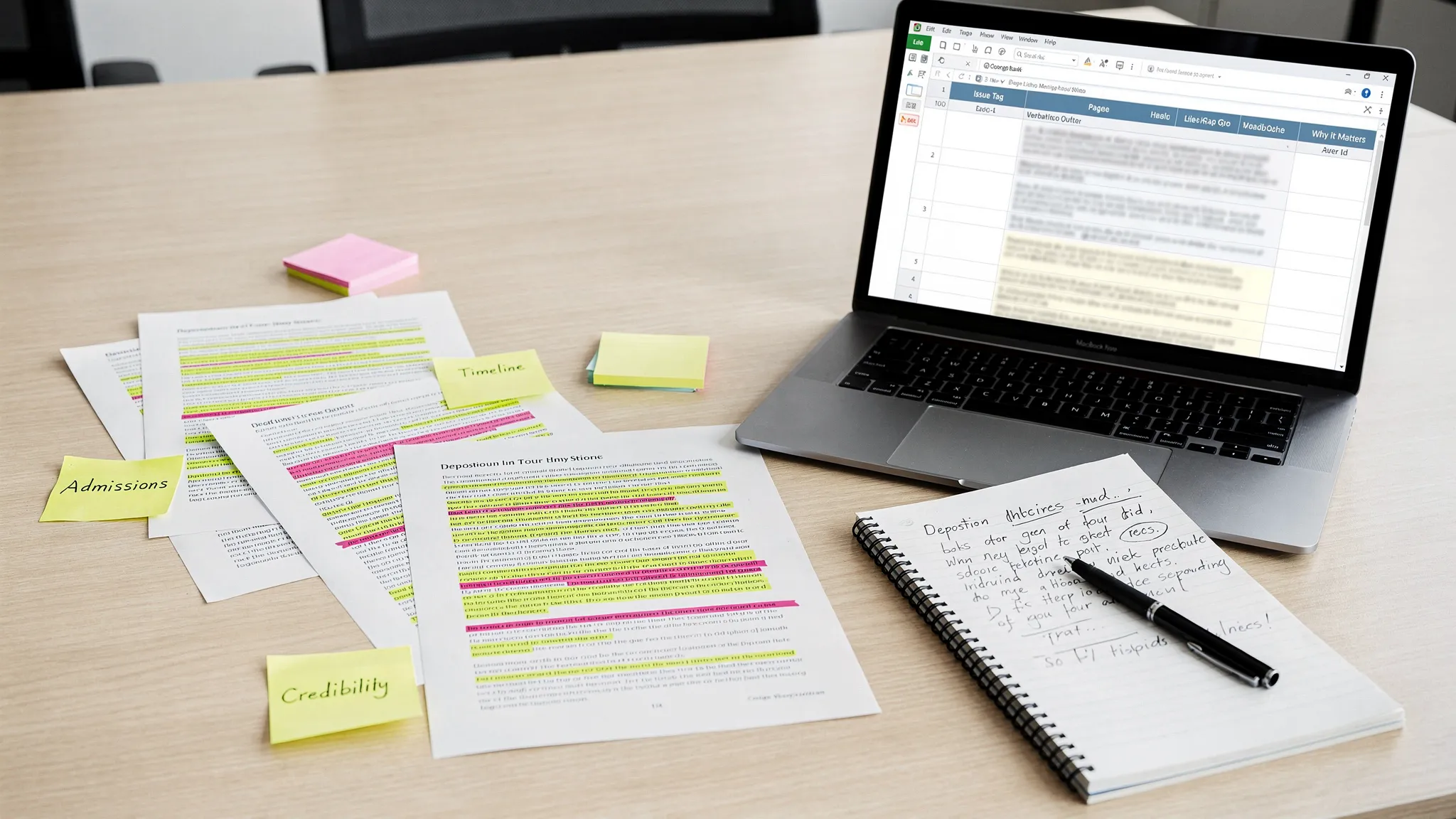

Between breaks: a 5-minute workflow that sharpens your next segment

Trials are won in the small windows, lunch, recess, and the moments when the witness steps down.

If you are stepping into a new matter or taking over as trial counsel midstream, it can help to think in phases, like a “first 30/60/90” plan for what you will stabilize, improve, and deliver. The structure in this 30/60/90 deck framework translates surprisingly well to building an internal trial plan (what you must master immediately, what you can refine next, and what you will optimize once the rhythm is set).

For day-to-day trial execution, many teams use AI to compress prep time during those windows, for example turning a stack of medical records into a usable medical summary, or generating a deposition outline keyed to the issues you need for your next witness. If your practice benefits from that kind of speed, TrialBase AI is designed to convert case documents into litigation-ready outputs (demand letters, medical summaries, deposition outlines, and more) in minutes, so you can spend your limited in-court time on judgment and delivery.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “win the record” mean for a lawyer in trial? It means making a transcript that clearly shows your legal basis, the court’s rulings, what evidence was offered, and why disputed points mattered.

How specific does an objection need to be? Specific enough that the judge can rule and a later reader can see the exact basis. “Objection, hearsay” is stronger than “objection,” and adding a brief fix can be even better.

Do I need to make offers of proof when evidence is excluded? Often, yes. If the substance of the excluded evidence is not in the record, it is harder to argue harm later.

What is the fastest way to improve trial performance? Build repeatable micro-habits: speak in complete record-friendly sentences, use consistent exhibit language, and run a short reset after every sidebar or ruling.

Turn trial time into a transcript that works for you

If your team is spending nights stitching together medical timelines, drafting demand letters, or building deposition outlines from raw documents, you are burning the hours you need for witness control and real-time judgment. TrialBase AI helps you transform uploaded case documents into litigation-ready work product in minutes, so you can focus on the courtroom habits that actually win the record.

Explore the platform at ai.trialbase.com.

.png)