Law and Litigation: A Plain-English Roadmap for Clients

Most people meet law and litigation for the first time when something has already gone wrong: a crash, a contract dispute, a termination, a business breakup. The process can feel like a black box filled with deadlines, unfamiliar documents, and stressful decisions.

This plain-English roadmap explains what litigation is, what typically happens at each stage, and what you can do as a client to help your lawyer help you.

What “litigation” actually means (and what it is not)

Litigation is the formal process of resolving a dispute through the court system. It usually follows rules set by your state court or, in federal cases, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Litigation is not the same thing as “going to trial.” In many civil cases, the majority of work happens before trial, and many disputes resolve through settlement, mediation, or dismissal after key facts and legal issues become clear.

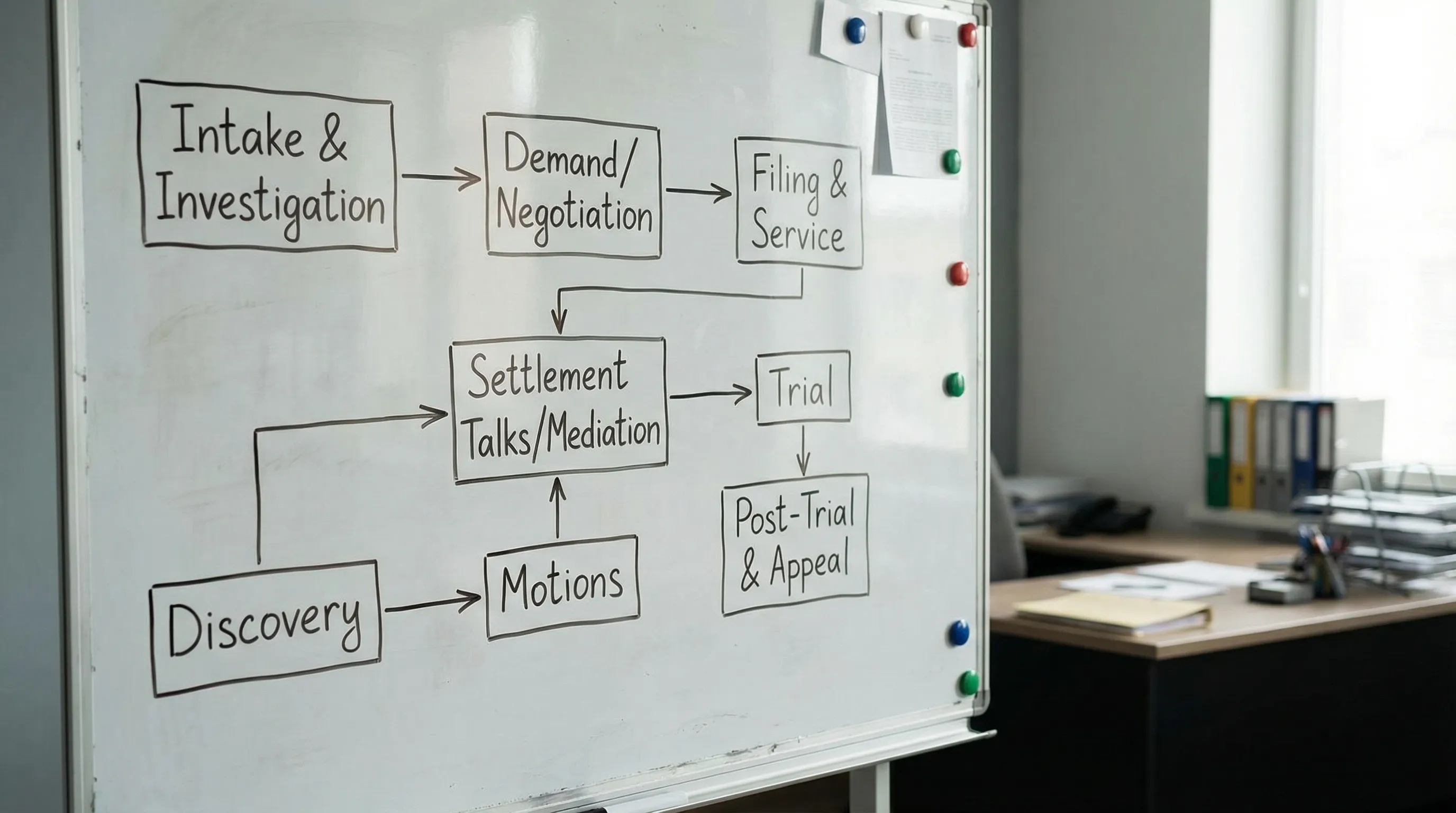

The litigation timeline at a glance

Every case is different, but most civil cases move through a familiar path.

Here is what that path often looks like from a client’s perspective:

| Stage | What it is | What you may be asked to do | Typical time horizon (varies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intake and investigation | Your lawyer learns the facts and law | Share documents, timeline, witnesses | Days to weeks |

| Demand and negotiation | Attempt to resolve pre-suit (common in injury and some business matters) | Approve strategy, review demand letter | Weeks to months |

| Filing and service | A complaint is filed and served | Confirm names, addresses, key facts | Days to weeks |

| Discovery | Exchange evidence (documents, questions, depositions) | Search for records, answer questions, prepare for deposition | Months to over a year |

| Motions | Requests for the judge to decide issues | Provide declarations or clarifications | Weeks to months |

| Settlement or mediation | Structured negotiation with counsel (and sometimes a mediator) | Evaluate offers, weigh risks, make decisions | Any time, often after discovery |

| Trial | Judge or jury decides the outcome | Testify if needed, be available, stay prepared | Days to weeks |

| Post-trial and appeal | Cleanup, enforcement, or appeal | Decide whether to appeal, assist with enforcement | Months to years |

Step 1: Intake, your story becomes a case theory

Early on, your lawyer is turning your lived experience into something the legal system can evaluate: a timeline, a set of claims or defenses, and a plan for proof.

The most helpful thing you can provide is clarity. A clean chronology, even if it is incomplete, is gold. If you are unsure of details, say so. Guessing can create credibility problems later.

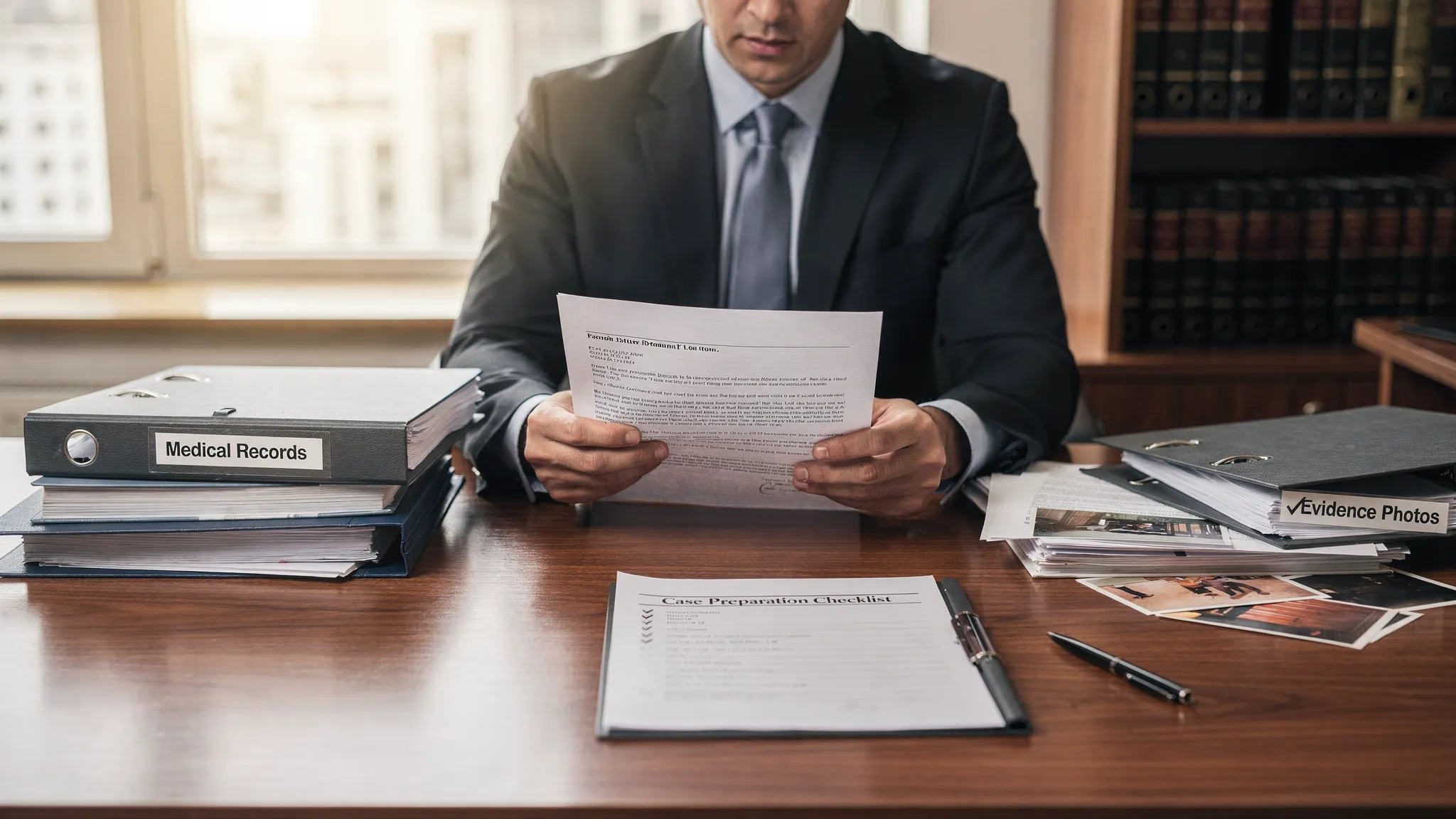

Step 2: The documents that drive outcomes

Litigation is built on records. Even strong cases can weaken if documentation is thin or inconsistent.

Common examples include emails and messages, contracts and invoices, photos, incident reports, employment records, and, in injury cases, medical records and billing.

If your dispute involves health issues, it can also help to keep a consistent paper trail of care and symptoms. Some people also maintain broader health baselines through clinician-reviewed lab programs (for example, Vitals Vault for biomarker testing and ongoing protocols). Whether that type of data is relevant depends on the facts and your lawyer’s strategy, but the principle is the same: objective records matter.

Step 3: Discovery, where the case gets real

Discovery is the evidence-exchange phase, and it is usually the longest and most expensive part of civil litigation.

This is where you may see:

- Document requests (you produce records, and the other side produces theirs)

- Written questions (interrogatories) and sworn written answers

- Depositions (live, under-oath questioning)

Depositions are often the moment clients fear most. In practice, they are manageable with preparation. Your lawyer will help you understand the process, review likely topics, and practice answering in a truthful, concise way.

Step 4: Motions and legal arguments

While facts matter, courts also decide cases based on rules and legal standards. Motions are how lawyers ask the judge to:

- Dismiss claims that do not meet legal requirements

- Compel discovery if the other side refuses to produce

- Exclude improper evidence

- Enter judgment when there is no genuine dispute over key facts

If you are asked to sign a declaration or verify facts, treat it seriously. Those statements can become evidence.

Step 5: Settlement, mediation, and the decision points

Settlement is not “giving up,” and going to trial is not automatically “standing your ground.” These are strategy choices.

A practical way to think about settlement is risk management: what you might win, what you might lose, the cost to get there, and the time it takes. Your lawyer can advise, but only you can decide what tradeoffs you are willing to accept.

What you can do to help your case (without micromanaging it)

Clients often ask what they can do that actually moves the needle. These habits typically help across most case types:

- Preserve evidence early: do not delete messages, emails, photos, or files.

- Centralize your records: keep one folder (digital or physical) with clean filenames and dates.

- Be consistent: align what you say in intake, in discovery, and under oath.

- Stay off the battlefield: avoid posts, comments, or direct contact that can be used against you.

- Ask for the plan: “What happens next, and what do you need from me by when?”

Where modern litigation support tools fit

Even in a “simple” case, lawyers juggle a mountain of documents: medical records, discovery responses, deposition transcripts, and correspondence. Turning that material into litigation-ready work product (like demand letters, medical summaries, or deposition outlines) takes time and careful attention.

Platforms like TrialBase AI are designed to support legal teams by analyzing uploaded documents and generating case-prep outputs in minutes, such as demand letters, medical summaries, deposition outlines, and trial materials, while keeping everything in a unified workflow for collaboration. For clients, the value is indirect but meaningful: faster organization, fewer bottlenecks, and more time for your lawyer to focus on strategy.

A final note on expectations

Law and litigation reward patience and precision. You do not need to know every rule, but you do need to be responsive, organized, and honest. If you do those three things, you give your lawyer the best raw material to build a persuasive case and negotiate from strength.

.png)