Discovery Process in Litigation: Step-by-Step Guide

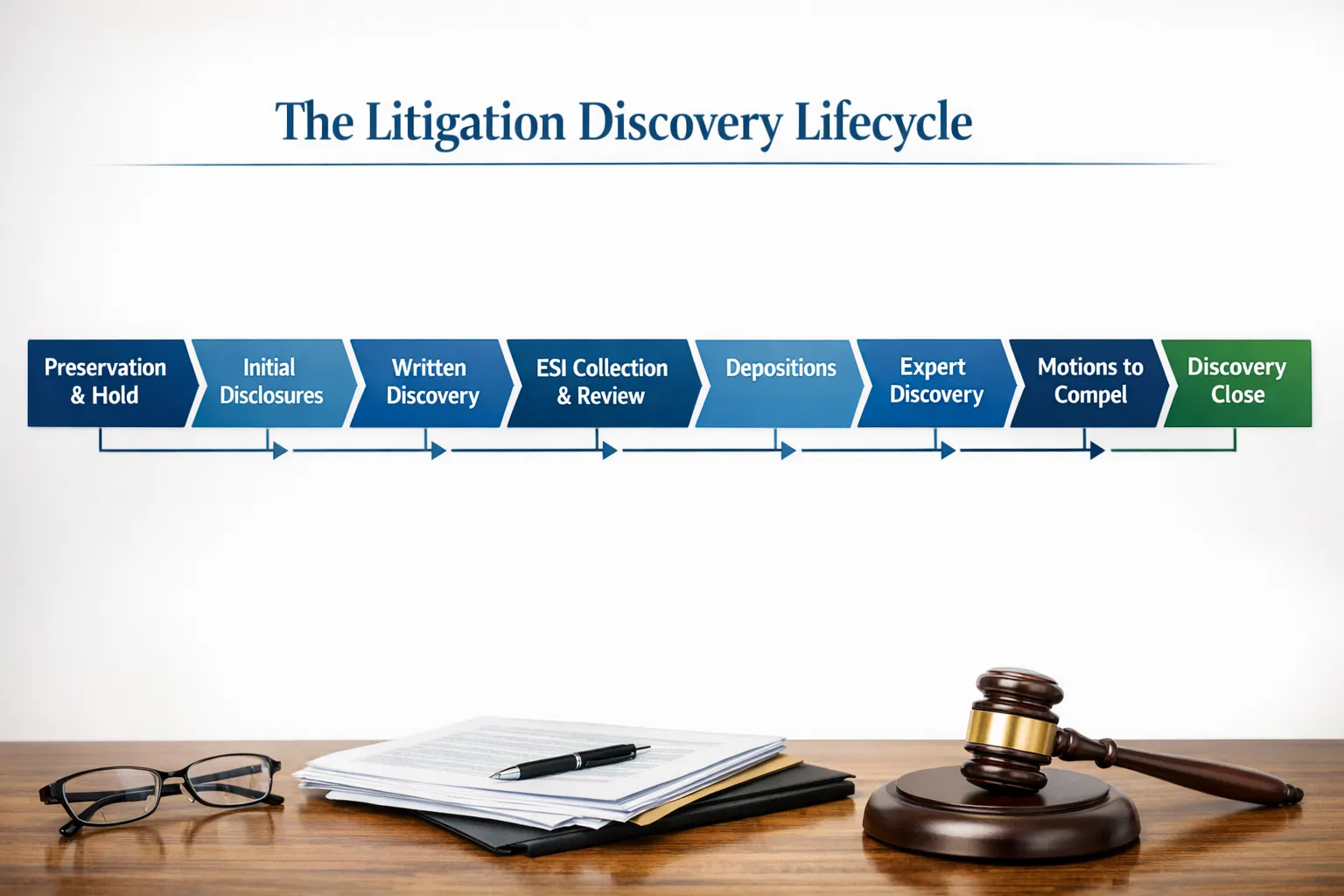

Discovery is where most civil cases are won or lost. It is the phase that turns pleadings into proof, surfaces the documents and testimony you need to evaluate exposure, and creates the record you will later use for dispositive motions, settlement leverage, and trial.

This guide walks through the discovery process in litigation, step by step, with practical tips (and common traps) you can use immediately.

What is the discovery process in litigation?

The discovery process is the court-governed exchange of information between parties, plus the tools used to obtain evidence from non-parties. Discovery typically includes:

- Required disclosures (in many jurisdictions)

- Written discovery (interrogatories, requests for production, requests for admission)

- Electronically stored information (ESI) preservation and collection

- Depositions

- Expert discovery

- Subpoenas to non-parties

- Discovery motions and enforcement (protective orders, motions to compel, sanctions)

In U.S. federal court, discovery is primarily governed by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP), especially Rule 26 (scope, proportionality, disclosures) and Rule 37 (motions to compel and sanctions). State rules often mirror the same concepts but differ on timelines, disclosure requirements, and limits.

Step 0: Align discovery with your case theory (before you serve anything)

A common mistake is treating discovery as a checklist. Effective discovery starts with a case theory and a proof plan.

Ask:

- What elements must we prove (or negate)?

- What issues will drive value (liability, causation, damages, comparative fault, notice, punitive exposure)?

- What evidence will actually move the other side, the judge, or the jury?

From there, build a targeted map of:

- Custodians (people, departments, third parties)

- Systems (email, EHR/EMR, claims platforms, HR systems, payroll, CRM, telematics, body cam, etc.)

- Documents and data types (incident reports, training materials, maintenance logs, billing, prior complaints, photographs, metadata)

- Testimony you need (party reps, treating doctors, experts, corporate designees)

This “discovery map” becomes the backbone for your requests for production, deposition plan, and subpoena list.

Step 1: Preservation and litigation holds

Discovery begins the moment litigation is reasonably anticipated. Preservation failures can create leverage for the opposing side, or worse, lead to sanctions.

Key moves early:

- Send a tailored preservation letter (especially for ESI like surveillance video, vehicle data, audit logs, and communications)

- Identify high-risk evidence with short retention windows (camera footage, call recordings, messaging apps)

- For your own client, implement a litigation hold and document compliance

In federal court, proportionality matters, but so does defensibility. A narrowly tailored hold that misses a key system is still a problem.

Step 2: Rule 26(f) meet-and-confer (and discovery plan) in federal court

In federal cases, the Rule 26(f) conference is where discovery can become efficient or chaotic. This is where parties typically address:

- The discovery schedule

- ESI issues (preservation, search terms, formats of production)

- Privilege (clawback agreements, FRE 502(d) orders)

- Protective orders and confidentiality designations

- Phased discovery (for example, liability first, damages later)

Practical tip: treat the meet-and-confer like a negotiation. If you want native files, specific metadata, or a phased plan, you need to ask clearly and tie it to proportionality and case needs.

Step 3: Initial disclosures (where applicable)

Many jurisdictions require early disclosures of:

- Likely witnesses with discoverable information

- Documents and ESI you may use to support claims or defenses

- Damages computations (in some contexts)

- Insurance information (often in federal cases)

These are not just formalities. They signal your readiness, define the early record, and can box in later “surprise” witnesses.

Step 4: Written discovery (the core exchange)

Written discovery is where you build the documentary record and lock in positions.

Interrogatories (who, what, when, why)

Interrogatories are best for:

- Identifying witnesses and custodians

- Establishing timelines and decision-makers

- Pinning down defenses and affirmative contentions

- Discovering policies, procedures, and training foundations

In federal court, see FRCP Rule 33.

Drafting tip: use targeted interrogatories to force the other side to commit to a version of events you can test in depositions.

Requests for production (RFPs) (documents and ESI)

RFPs are where most of your case gets built. They should be written to:

- Capture the complete universe of documents (not just what the other side wants to hand over)

- Identify specific systems, custodians, and timeframes

- Demand production in usable formats (including metadata where appropriate)

In federal court, see FRCP Rule 34.

ESI tip: if the dispute will involve communications, versions, or timing, consider requesting native format and key metadata fields (and put it in writing early).

Requests for admission (RFAs) (narrowing issues)

RFAs are often underused. They are valuable for:

- Authenticating records

- Establishing basic facts that should not be contested

- Forcing denials you can later use for fees, sanctions, or impeachment (depending on rules)

In federal court, see FRCP Rule 36.

Step 5: ESI collection, review, and production (the reality of modern discovery)

Most discovery disputes today are really ESI disputes. Even small cases can involve:

- Emails and attachments

- Texts and chat platforms

- Cloud storage

- Social media

- Audit logs

- Mobile photos, videos, and metadata

You will usually encounter these production questions:

- What is the date range?

- Which custodians?

- Which systems?

- What search methods (keywords, analytics, TAR, etc.)?

- What format (TIFF/PDF/native)?

- What fields of metadata?

- How will privilege be handled?

Practical tip: be specific about “where” the evidence lives. Overbroad RFPs invite boilerplate objections. Well-scoped RFPs make it harder for the other side to hide behind burden arguments.

Step 6: Privilege review, privilege logs, and clawback agreements

Privilege is where discovery slows down and where mistakes get expensive.

Core concepts to manage:

- Attorney-client privilege vs work product

- Common interest and joint defense arrangements

- Inadvertent production and clawback terms

In many cases, parties negotiate clawback provisions and sometimes seek a protective order to reduce waiver risk. In federal cases, a FRE 502(d) order can be a powerful tool.

Practice point: privilege logs should be defensible and consistent. A vague or late log invites motion practice.

Step 7: Non-party discovery (subpoenas)

Non-party evidence often decides causation, damages, and credibility. Typical sources include:

- Medical providers and imaging centers

- Employers and payroll processors

- Prior incident locations and property managers

- Vendors, subcontractors, and maintenance companies

- Cell providers, platforms, and payment processors (case-dependent)

In federal court, subpoenas are governed by FRCP Rule 45.

Tip: build a subpoena tracker early. Non-party lead times, objection periods, and HIPAA compliance steps can quietly derail your schedule.

Step 8: Depositions (turn documents into admissions)

Depositions are where you pressure-test the story and secure usable testimony. Your deposition plan should be informed by what you learned from:

- Interrogatory answers

- Document productions

- ESI gaps (missing custodians, missing systems)

- Privilege logs

Common deposition categories:

- Party depositions (plaintiff, defendant)

- Fact witnesses (employees, responders, third-party observers)

- Corporate representative depositions (for example, 30(b)(6) in federal court, see FRCP Rule 30)

- Treating providers and retained experts

Practical tip: write deposition outlines that mirror your exhibit set. The fastest path to a clean record is structured questioning tied to authenticated documents.

Step 9: Expert discovery (where the case value hardens)

Expert discovery often determines whether a case settles and for how much. Typical steps include:

- Expert disclosures and reports

- Production of relied-upon materials

- Depositions of experts

- Motions to exclude or limit testimony (jurisdiction-specific standards)

Tip: do not wait until expert reports to organize the medical and damages record. If medical chronology and billing are messy, expert work becomes slower, more expensive, and easier to attack.

Step 10: Discovery disputes, motions to compel, and protective orders

Discovery disputes are common, but they are also preventable with clear drafting and a disciplined meet-and-confer process.

Typical disputes involve:

- Overbreadth and proportionality objections

- Privilege assertions and incomplete logs

- ESI format fights and search term disagreements

- “No documents exist” responses that do not match the business reality

- Confidentiality designations (over-designation, attorney’s eyes only)

In federal court, motions to compel and sanctions are addressed under FRCP Rule 37.

Practical tip: judges reward specificity. When moving to compel, identify the exact request, the response, the deficiency, the meet-and-confer history, and the narrow relief you want.

Step 11: Discovery close, pretrial disclosures, and trial readiness

As discovery closes, your goal shifts from “collect everything” to “curate what matters.” This is where you:

- Finalize exhibit lists and authentication

- Lock in testimony designations

- Confirm foundational witnesses for key records

- Identify gaps that require stipulations or targeted follow-up

If you wait until pretrial to realize you never obtained a complete policy manual, an unredacted incident report, or the underlying imaging, you may be stuck.

A practical timeline: what happens when (typical civil case)

Timelines vary by jurisdiction and case complexity, but this is a common progression you can adapt.

| Phase | What typically happens | Main risk if mishandled |

|---|---|---|

| Early case | Preservation, hold, initial disclosures (where required) | Spoliation claims, missing short-retention evidence |

| First wave | Interrogatories, RFPs, initial subpoenas | Overbroad requests, delayed non-party responses |

| Mid case | Rolling productions, ESI disputes resolved, key fact depositions | Depositions taken before the record is complete |

| Later | Expert discovery, expert depositions, dispositive motions | Disorganized damages record, expert vulnerability |

| Close | Final supplementation, exhibit authentication, pretrial prep | Trial surprises, missing foundations |

Common discovery mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Treating boilerplate objections as meaningful

Objections like “overbroad,” “unduly burdensome,” and “not proportional” are easy to write and sometimes hard to evaluate. Push for specifics: which custodians, which systems, what volume, what cost, what alternative scope?

Failing to define production formats

If you need metadata, native files, or load files for review, address it early. Otherwise, you may receive flattened PDFs that are harder to analyze and harder to use.

Taking depositions too early

A deposition taken before key custodians and systems have produced often leads to a second deposition fight, or worse, missed impeachment.

Letting medical records stay unstructured

In injury cases, the medical record can be the case. If records are not summarized, chronological, and tied to damages themes, discovery becomes slower and settlement evaluation becomes guesswork.

Losing track of what you asked for

Discovery is a workflow problem as much as it is a legal problem. Without a system to track requests, deficiencies, follow-ups, and what each production contains, you will miss gaps.

Where AI can help (without replacing legal judgment)

Discovery still requires attorney strategy and defensible choices. But modern tools can reduce the time spent on repetitive, high-volume work.

For example, TrialBase AI is designed for litigation support from intake to verdict. After you upload documents, it can help generate litigation-ready outputs in minutes, including:

- Medical summaries to quickly structure records into a usable chronology

- Deposition outlines based on your case materials, so you can move from documents to examination prep faster

- Demand letters and other case-ready drafts to support settlement positioning

- Trial materials preparation support when you need to turn the record into presentation-ready work product

- Team collaboration and a unified workspace to keep discovery inputs and outputs organized

The value in discovery is not only speed. It is consistency, coverage (fewer missed issues), and the ability to iterate as new productions arrive.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does the discovery process take in litigation? Discovery length depends on the court’s scheduling order, case complexity, ESI volume, and number of witnesses. Many civil cases run discovery for several months to over a year, with rolling productions and depositions scheduled throughout.

What are the main tools used in the discovery process? The most common tools are initial disclosures (where required), interrogatories, requests for production, requests for admission, subpoenas to non-parties, depositions, and expert discovery.

What happens if a party refuses to produce documents in discovery? The requesting party typically must meet and confer, then may file a motion to compel. Courts can order production and, in some situations, award fees or impose sanctions depending on the rules and the conduct.

What is proportionality in discovery? Proportionality limits discovery to what is reasonable in light of the case needs, including the importance of the issues, amount in controversy, access to information, parties’ resources, and whether the burden outweighs the likely benefit. In federal court, proportionality is central to Rule 26.

Do I need metadata in document production? Sometimes. If timing, authorship, versions, or communication chains matter, metadata and native files can be critical. If your case only requires the content of static documents, PDFs may be sufficient. The key is to decide early and specify the format in your requests.

Turn discovery materials into case-ready work product faster

If discovery is consuming attorney hours that should be spent on strategy, TrialBase AI can help you convert documents into litigation-ready outputs quickly. Upload your records and generate medical summaries, deposition outlines, demand letters, and more, all designed to support a streamlined litigation workflow.

Explore TrialBase AI at ai.trialbase.com.

.png)