Discovery Process Explained: Timelines and Best Practices

Discovery is where most civil cases are won or lost, not because it is glamorous, but because it determines what facts actually make it into the record. Miss a deadline, mishandle preservation, or produce documents in the wrong format, and you can create avoidable motion practice, cost, and sanctions risk. Run it well, and you narrow issues early, strengthen valuation, and walk into depositions and mediation with leverage.

Below is a practical, litigation-forward explanation of the discovery process, including common timelines (especially in federal court) and best practices that help teams stay organized from first hold notice to final pretrial disclosures.

What “discovery” actually includes (and what judges care about)

In most civil matters, discovery is the phase where parties exchange information relevant to claims and defenses. The tactical goal is not to collect everything, it is to obtain admissible proof and impeachment material while controlling cost and risk.

Discovery commonly includes:

- Initial disclosures (in many federal cases) and early case information exchanges

- Written discovery: interrogatories, requests for production, requests for admission

- Depositions: party, fact, and expert

- Third-party discovery: subpoenas (documents and testimony)

- Expert discovery: reports, data considered, depositions

- ESI issues: preservation, collection, search methods, production format, metadata, privilege filtering

In federal court, the center of gravity is still proportionality and cooperation. The 2015 amendments to FRCP Rule 26(b)(1) made proportionality explicit, and judges increasingly expect parties to show they scoped discovery rationally.

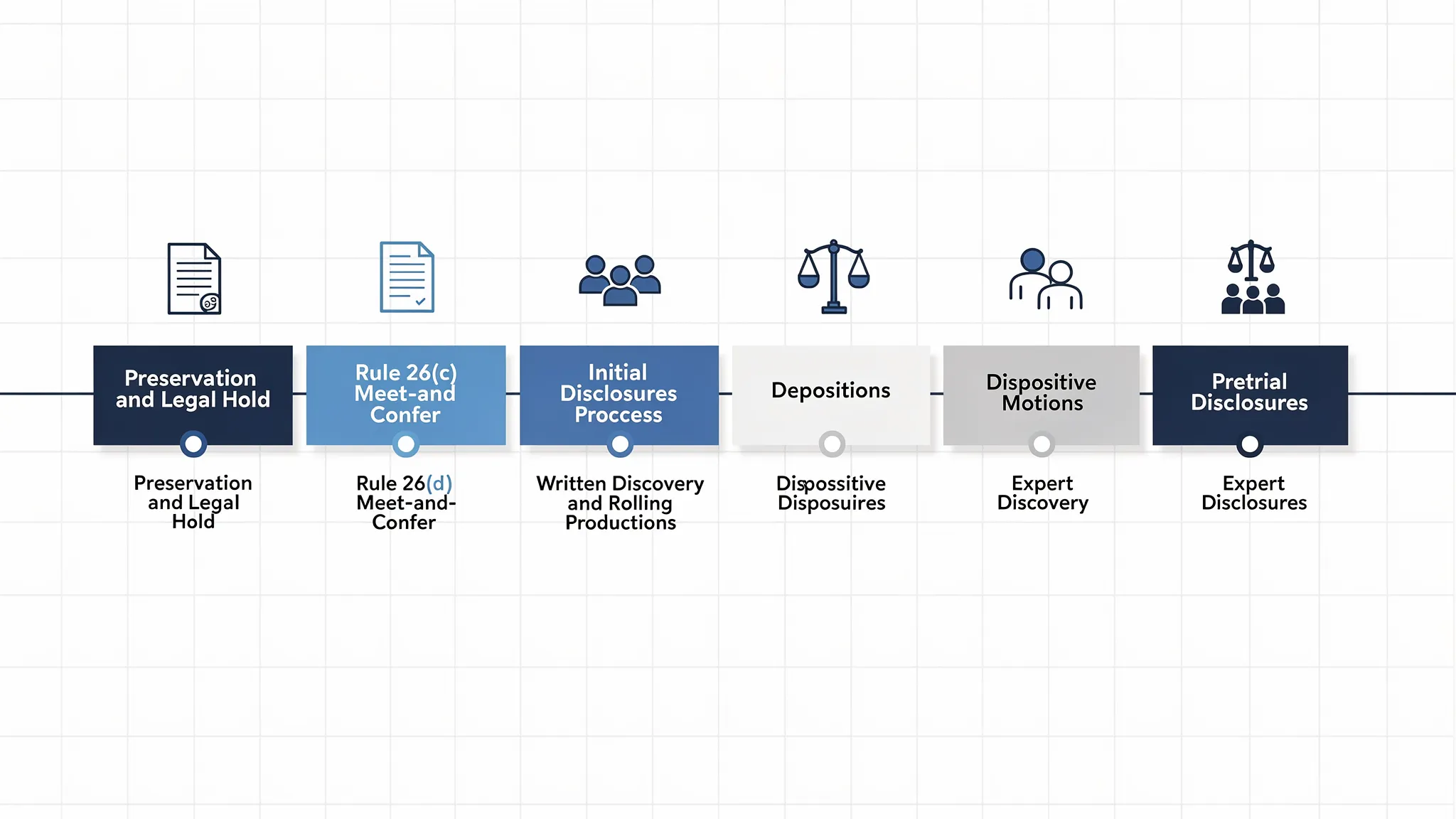

Discovery timelines: a practical, federal-court oriented map

Timelines vary by jurisdiction, judge, case complexity, and whether there is expedited discovery. But many federal civil cases roughly follow a familiar sequence: Rule 26(f) conference, scheduling order, written discovery and ESI productions, depositions, expert discovery, and pretrial disclosures.

Typical timeline anchors (federal civil cases)

Use this as a planning baseline, then adjust to your court’s local rules and the scheduling order.

| Phase | Key trigger | Typical window (varies widely) | Practical deliverable | Common pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preservation and legal hold | Reasonably anticipated litigation | Immediately (days, not weeks) | Hold notice, custodian list, data map | Overbroad holds that no one follows, incomplete custodian identification |

| Rule 26(f) conference | Parties confer | Often early in case, before scheduling order | Discovery plan, ESI topics, proposed deadlines | Treating it as a formality, no real ESI planning |

| Initial disclosures (Rule 26(a)(1)) | Rule 26(f) conference | Often within ~14 days after 26(f), unless exempted or altered | Witnesses, documents, damages, insurance | Incomplete damages support, missing document categories |

| Written discovery served | After scheduling order (or earlier if allowed) | Early-to-mid discovery period | Interrogatories, RFPs, RFAs | Boilerplate requests/objections, unclear definitions |

| Responses due | Service of requests | Commonly 30 days under FRCP Rule 33 and Rule 34 | Verified responses, objections, production plan | Missing the deadline, not stating whether documents are being withheld based on objections |

| Rolling productions | Collection/search starts | Ongoing (often staged) | Production sets with load files/format specs | Producing without consistent Bates strategy, inconsistent metadata, no QC |

| Depositions | After meaningful productions | Mid-to-late discovery | Depo outlines, exhibit sets, deposition summaries | Depositions taken before key docs arrive, exhibit chaos, weak impeachment prep |

| Expert disclosures | Scheduling order | Often late discovery | Reports, underlying data | Experts not aligned to the evidentiary record, late data handoffs |

| Expert depositions | After reports | Late discovery | Expert cross themes, Daubert record | Not locking methodology, not pressing on missing data |

| Discovery cut-off | Scheduling order | Fixed | Close-out checklist | “Oh no” moments (missing custodians, incomplete privilege review) |

| Pretrial disclosures | Rule 26(a)(3) deadlines | Often ~30 days before trial unless ordered otherwise | Witness/exhibit lists, objections | Scrambling to reconcile discovery record with trial presentation |

If you want one operational takeaway: treat the scheduling order as a project plan. Every week without preservation, collection, and a production cadence increases downstream deposition and expert risk.

Preservation first: legal holds, custodians, and Rule 37(e) risk

The earliest discovery win is often avoiding discovery disaster.

What to do immediately

Start with a defensible preservation workflow:

- Identify likely custodians and key systems (email, messaging apps, cloud drives, case management tools, mobile devices, shared drives)

- Issue a written legal hold with plain-language instructions

- Suspend auto-deletion where feasible (or preserve through collection/exports)

- Schedule custodian interviews early so you can map where “the truth” actually lives

Under FRCP Rule 37(e), the analysis focuses on whether ESI that should have been preserved was lost because reasonable steps were not taken, and whether loss prejudiced the other party (with more severe measures tied to intent). Courts expect you to behave like you understood your client’s systems.

Best practice: create a “data map” you can defend

A data map is not a glossy chart. It is a working document listing systems, owners, retention settings, and collection method. It helps you answer uncomfortable questions quickly (for example, “Who used Teams chat for this project, and where is it retained?”).

The Rule 26(f) meet-and-confer: where you prevent later fights

Many discovery disputes are really “we never agreed on the basics” problems.

At the meet-and-confer, aim to align on:

- The scope of custodians and date ranges

- The ESI protocol (sources, search methods, and production format)

- Privilege handling, including clawback

- Phasing (what gets produced first so depositions are meaningful)

If you need a credibility benchmark for ESI best practices and cooperation concepts, many litigators look to the Sedona Conference publications as persuasive guidance (even when not binding).

Written discovery best practices: draft for answers you can use

Requests for production: specificity beats volume

RFPs should be specific enough that you can enforce them and practical enough that they will be answered. Overbroad requests create delay and motion practice. Under FRCP Rule 34, parties must state with specificity the grounds for objections and indicate whether responsive materials are being withheld.

A strong RFP package typically:

- Uses defined time windows tied to events

- Targets a short list of “decision” categories (contracts, change orders, incident reports, communications with regulators, medical records, billing, photos/video)

- States production format expectations early (native vs TIFF/PDF, metadata fields, load files)

Interrogatories: use them to lock the story

Interrogatories are most effective when they force the opposing party to:

- Identify the witnesses who support each contention

- Specify dates, communications, and documents

- Admit or deny key factual propositions that shape motion practice and depositions

Requests for admission: narrow, narrow, narrow

RFAs are often the cheapest way to reduce trial risk. The best RFAs are not argumentative. They target authenticity, foundational facts, and timeline points that you do not want to re-prove later.

Managing productions: cadence, QC, and privilege are the difference-makers

Discovery breakdowns frequently happen in the gap between “we’ll produce” and “we produced.” Build a predictable cadence.

Production best practices that reduce re-work

- Set a rolling production schedule (for example, every two weeks) and stick to it

- Standardize naming and Bates rules before the first export

- Run QC checks (missing attachments, date range gaps, broken families, empty metadata)

- Track what has been produced by custodian, source, and issue tag so you can answer “Did we produce X?” in seconds

Privilege and clawback: decide early, document it

Privilege review is where time disappears and mistakes compound.

Consider a clawback agreement or protective order provisions that align with Federal Rule of Evidence 502, which is designed to reduce waiver risk from inadvertent production when properly structured.

Depositions: schedule them after you have the documents you need

A deposition taken before meaningful production is often a paid fact-finding interview. Sometimes you must do it (for example, to support preliminary injunction issues), but it should be a conscious tradeoff.

To make depositions count:

- Build outlines around document sequences, not just topics

- Create exhibit sets that tell a timeline (then add impeachment exhibits)

- Identify “must-lock” testimony (who knew what, when, what was done, and why)

- Prepare a short list of admissions that matter for summary judgment or valuation

This is also where teams can save major time by turning document collections into litigation-ready work product. Tools such as TrialBase AI are designed to help legal teams transform uploaded records into outputs like medical summaries, deposition outlines, and demand letters, which can shorten the cycle from production receipt to deposition readiness.

Expert discovery: protect deadlines by aligning data early

Expert work is downstream from your document record. If experts do not get complete data early, you risk late supplements, rushed analysis, and avoidable motion practice.

Operationally, the best practice is simple: once you know the expert issues, maintain a dedicated “expert packet” that stays current as rolling productions arrive.

Discovery as a project: the best teams run it like one

Discovery is legal, but it is also logistics. The biggest improvements usually come from workflow discipline.

A lightweight discovery management system should track:

- Deadlines from the scheduling order and local rules

- Custodian list, data sources, and collection status

- Requests served, responses due, deficiency letters, and meet-and-confers

- Production sets, Bates ranges, and privilege log status

- Deposition scheduling, exhibits, and follow-up items

Many firms now apply automation wherever it reduces repetitive coordination. For example, some legal organizations also use AI agents in other parts of the business, such as Kakiyo’s AI SDR for LinkedIn outreach to streamline business development conversations, while keeping litigation discovery workflows focused on defensibility and court-ready output.

A discovery “best practices” checklist you can actually use

Here is a practical checklist that maps to the most common discovery failure points:

| Stage | Best practice | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation | Issue legal hold early, interview custodians, document steps | Reduces spoliation risk and later credibility issues |

| Meet-and-confer | Agree on ESI protocol, scope, format, and privilege handling | Prevents avoidable motion practice and re-productions |

| Written discovery | Draft targeted RFPs and contention interrogatories | Drives usable facts instead of noise |

| Production | Set rolling cadence, consistent Bates strategy, and QC gates | Keeps depositions and experts on schedule |

| Privilege | Use consistent review criteria and a clear clawback plan | Prevents waiver fights and costly re-review |

| Depositions | Depose after key documents, use timeline exhibits, lock admissions | Increases settlement leverage and trial readiness |

| Close-out | Confirm completeness (custodians, date ranges, sources), finalize logs | Avoids last-minute emergencies and sanctions exposure |

Final thought: discovery is where speed and defensibility can coexist

Fast discovery is not the same as sloppy discovery. The goal is a defensible process that produces the right documents early enough to drive decisions: whether to move to compel, whether to narrow issues, whether to mediate, and what your trial themes will be.

If you treat discovery as a managed workflow (preservation, scope, cadence, QC, deposition readiness) you will spend less time fighting about process and more time using facts to win.

.png)