Demand for Discovery: Deadlines, Triggers, and Next Steps

A missed discovery deadline rarely fails quietly. It shows up later as an avoidable motion, a blown deposition prep timeline, or settlement leverage you never had. A well-timed demand for discovery is less about “sending paper” and more about triggering predictable obligations, then managing the clock and follow-through.

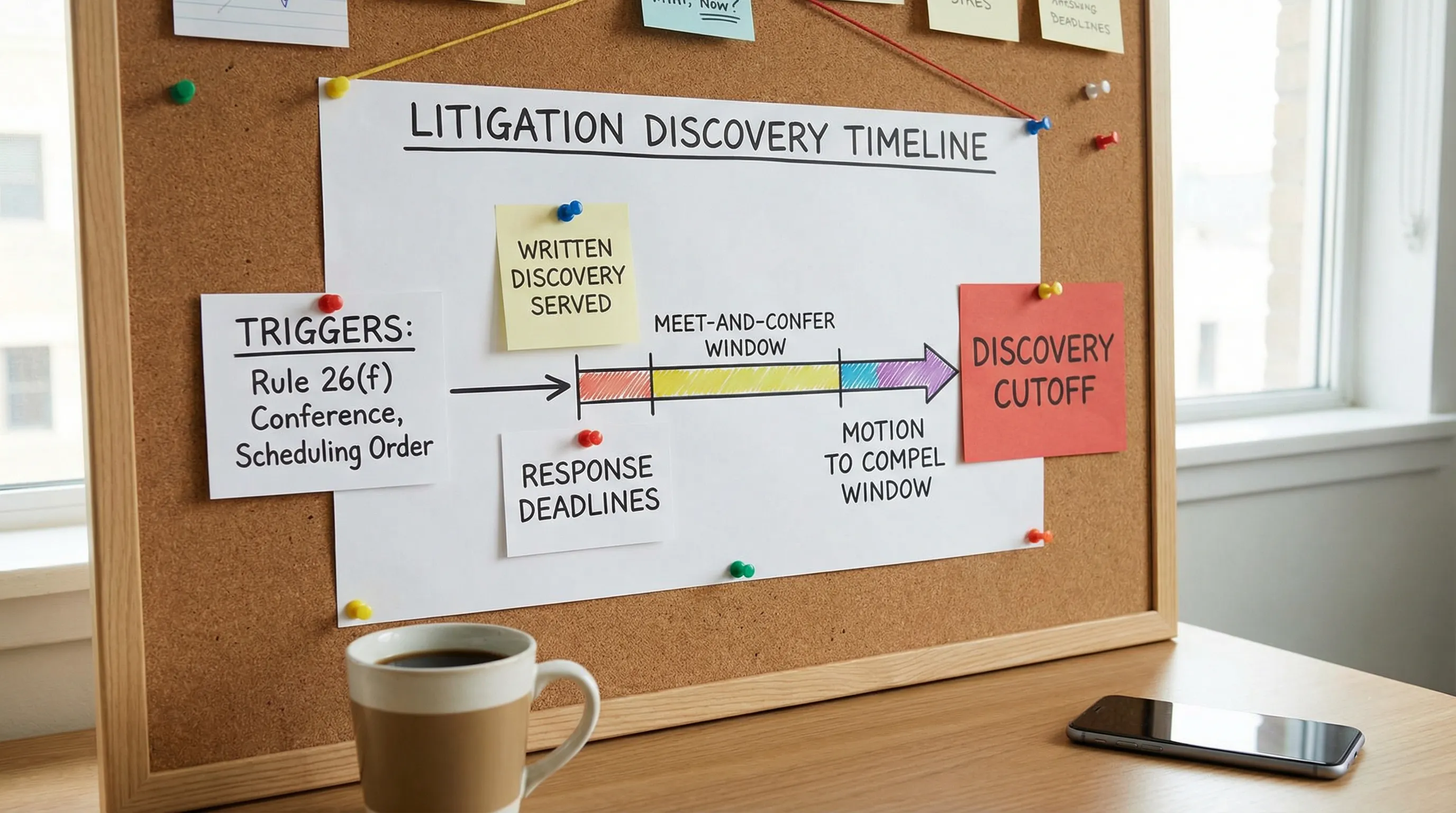

Below is a practical, jurisdiction-aware way to think about deadlines, triggers, and next steps (with federal rule references where helpful). This is general information, not legal advice, and you should always confirm your local rules and case orders.

What a “demand for discovery” usually means

In practice, “demand for discovery” is shorthand for serving formal discovery or invoking a discovery right under your forum’s rules, such as:

- Interrogatories

- Requests for production (RFPs)

- Requests for admission (RFAs)

- Notices/subpoenas for depositions and records (including ESI)

The goal is not just to obtain information, but to start enforceable timelines and create a record that supports meet-and-confer efforts and, if needed, a motion to compel.

The big triggers: when discovery starts (and when it does not)

Discovery timing is dictated by (1) rules, (2) the court’s scheduling order, and (3) any stipulations.

1) Case initiation and service

Service of the complaint (or initial appearance in some jurisdictions) often starts the broader litigation timeline, but it does not always mean discovery is immediately “open.” In federal court, discovery generally cannot be served until after the Rule 26(f) conference (with narrow exceptions).

2) The Rule 26(f) conference and scheduling order (federal)

In federal cases, the Rule 26(f) conference is a key trigger. After that point, parties can serve discovery requests. A Rule 16 scheduling order then becomes the practical “source of truth” for:

- Discovery cutoff

- Expert deadlines

- Dispositive motion deadlines

- Pretrial submissions

3) Court-specific constraints

State courts vary widely. Some allow discovery with the initial pleading; others require a waiting period or set sequences (for example, certain written discovery before depositions). Many also have mandatory disclosures, case management conferences, or local standing orders that effectively shift your real deadlines.

Core deadlines you should calendar immediately

Even when your matter is state-based, these federal benchmarks help create a reliable internal checklist.

| Discovery event | Typical federal timing | Rule reference (federal) | Practical takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serve written discovery (interrogatories, RFPs, RFAs) | After Rule 26(f) conference | FRCP 26(d) | Don’t draft in a vacuum, align requests to what you must prove and to your deposition plan. |

| Respond to interrogatories | 30 days after service (often 33 with service method considerations) | FRCP 33(b)(2) | Track response due date and build in time for deficiency review. |

| Respond to RFPs | 30 days after service | FRCP 34(b)(2)(A) | Confirm whether objections must be stated with specificity and whether productions must be rolling. |

| Respond to RFAs | 30 days after service | FRCP 36(a)(3) | Non-response can mean admissions, calendar these aggressively. |

| Initial disclosures (if applicable) | As set by rule/order | FRCP 26(a)(1) | Treat disclosures as both evidence map and discovery roadmap. |

| Duty to supplement | Ongoing | FRCP 26(e) | Plan “supplement checkpoints” after key events (new records, new experts, new damages). |

Two calendar tips that prevent most problems:

- Calendar both the response due date and a deficiency review date (for example, 7 to 10 days later), so you have time to meet and confer before motion deadlines.

- Calendar the discovery cutoff as a “serve-by” deadline, not a “finish-by” deadline. You need runway for responses, disputes, and compelled production.

What should trigger your next discovery step

Strong discovery is iterative. These common events should trigger a fresh “next step” review.

When you receive a partial production

Partial production is normal, but it should trigger a fast check:

- Are there obvious gaps (date ranges, providers, custodians, file types)?

- Do the Bates ranges match the cover letter description?

- Are you missing metadata, native files, or load files for ESI?

When medical or wage damages change

New treatment, new providers, new imaging, new time off work, or revised life-care planning should trigger targeted supplemental requests. Waiting until late discovery to “catch up” often forces you into rushed depositions.

When the defense answers with boilerplate objections

Boilerplate objections are a predictable trigger for a documented meet and confer. The earlier you press for clarity on scope, custodians, and search terms, the less likely you are to get a last-minute dump.

When a deposition is scheduled

Deposition planning should trigger:

- A focused RFP set tied to the witness and time period

- A short interrogatory set to lock in positions and locate documents

- An exhibit list built from what you already have, plus what you still need

Next steps: a workflow that keeps you out of motion practice (when possible)

A demand for discovery works best when it lives inside a simple operational loop.

Step 1: Define what you must prove

Before you serve, translate elements and defenses into “proof targets.” This keeps requests proportional and reduces objection risk. It also makes your deficiency letter tighter.

Step 2: Serve discovery in phases

One oversized set can invite delay. A phased approach is often faster:

- Phase 1: liability, key damages categories, insurance/coverage, core ESI

- Phase 2: follow-ups based on what Phase 1 reveals

Step 3: Build a deficiency record early

When responses land, your first pass should be about enforceability:

- Are objections specific?

- Are productions stated as complete?

- Are documents withheld on privilege with a usable log?

If you end up in motion practice, the quality of your deficiency record can matter as much as the underlying merits.

Step 4: Follow up like it is time-sensitive (because it is)

Discovery often fails on follow-up, not drafting. Consider using systems that enforce short response loops and reminders. The mindset is similar to sales outreach where speed-to-response matters. If you want an example of an automation approach in a different domain, Orsay AI for automated lead follow-up is built around fast, persistent follow-through, the same operational principle you need when chasing overdue discovery responses.

Step 5: Convert discovery into deposition and trial-ready materials

Discovery is only valuable if it becomes usable work product. As documents arrive, convert them into:

- Medical chronologies and issue summaries

- Deposition outlines keyed to exhibits

- Settlement-ready damages narratives

This is where disciplined organization can cut days off your prep cycle.

Common pitfalls that blow up deadlines

Waiting for “all records” before you start

You can serve targeted discovery early and supplement later. Waiting tends to compress deposition prep and increase disputes.

Treating the discovery cutoff as flexible

Courts vary, but many treat cutoffs seriously. If you need more time, raise it early with opposing counsel and, if needed, the court.

Not planning for ESI realities

If ESI is likely, discuss custodians, sources, formats, and search terms early. Late ESI fights are expensive and often end badly.

Frequently Asked Questions

When does the 30-day deadline start for discovery responses? It typically runs from service of the request, but details can change based on your jurisdiction, service method, and any stipulation or court order.

Can I serve discovery immediately after filing? Sometimes in state court, often not in federal court. In federal cases, you generally must wait until after the Rule 26(f) conference unless an exception applies.

What should I do if responses are late or incomplete? Document the deficiency, meet and confer promptly, and calendar motion deadlines. Many courts expect a meaningful attempt to resolve disputes before motion practice.

What is the best “next step” after receiving a production? Triage for gaps, build an exhibit list, and update your deposition outlines based on what the documents prove and what they still fail to address.

Litigation-ready outputs in minutes with TrialBase AI

When discovery starts coming in, speed matters. TrialBase AI helps legal teams turn uploaded documents into medical summaries, deposition outlines, demand letters, and other trial materials so you can move from production to preparation without losing days to manual drafting.

Explore TrialBase AI at ai.trialbase.com.

.png)